As politicians all over the world gather to prepare for the year ahead, COVID-19 will retain its place at the head of the global agenda. In 2022, the COVID-19 pandemic will continue to shape policy decisions, define the recovery of the world economy, and underpin freedom of travel. Government treasuries will have to contend with the consequences of the previous year, notably escalating fiscal deficits and unemployment rates, as well as face an uncertain future beset by hesitant investment and operational disruption. The soreness of the impact will be greater felt in those parts of the world where vaccination rates are lower, particularly Africa.

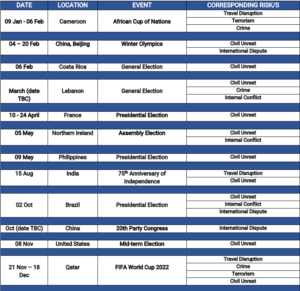

In the foreground, major elections in Europe (France), the Americas (Brazil), and the Middle East (Lebanon) are set to define the political landscape of their respective regions for the years ahead. Given the climate of global uncertainty under which they will take place, associated civil unrest is likely to be more pronounced than ever before. Elsewhere, internal conflict threatens continued escalation. The upcoming year will be a momentous one for the future of democratic stability in Ethiopia, Nigeria and Lebanon, as well as the security outlook in Afghanistan, where the Taliban seek to consolidate control.

Finally, beyond the world’s immediate gaze, geopolitical developments between China and the West are likely to be marked by acrimonious rhetoric, the intensification of existing trade disputes and an escalation in military antagonism. Altercations in the cyber domain are also expected to increase, with cyberattacks deriving from China and Russia set to be a growing concern for the West.

Europe

Key Event: French Presidential Election

Key Risks: Civil Unrest, Travel Disruption, Economic Instability, International Conflict

Underpinned by a surging current of social polarization, France must contend with the prospect of escalating civil unrest and internal conflict in 2022. As France’s centre and far-right vie for power in April’s presidential election, an incitation in hostilities is likely to follow, provoking mass rallies, demonstrations, and a possible surge in anti-Islamic sentiment. In the event of a far-right victory, civil unrest will threaten to erupt into violent disorder. France’s internal pressures will be compounded by regional concerns. The EU faces a year beset by economic uncertainty; Europe’s economic recovery plan will remain at the mercy of COVID-19, which threatens continued travel restrictions, supply-chain disruptions, and mounting fiscal deficits. In the political sphere, growing authoritarianism in Poland and Hungary will imperil both the functioning, and the very integrity, of the European Union. Further east, the diplomatic lagoon between Russia and Western Europe is likely to widen in an ongoing geopolitical feud that risks spilling over into international conflict.

In view of the upcoming presidential elections, France’s current president, Emmanuel Macron, is tipped for victory, but will face staunch opposition from Marine Le Pen, of the National Rally Party, as well as a number of independent candidates, including Éric Zemmour, a hard-line populist whose political profile is shaped by a strong anti-immigration stance. The election will open old wounds in France, security and immigration will remain topics of contention, and far-right candidates are likely to look for support among the “Gilet Jaunes” movement in their assault against the incumbent president. The electoral campaign is expected to be heated; the first rallies held at the end of this year were met by fierce counter protests and violence, posing risks to locals and travellers alike. As the activity of France’s political far-right organisations intensifies, so will the harassment of the country’s large migrant population. Macron will seek to use his remaining months in power to restore the French economy and push for social welfare reforms in a bid to elicit much needed public support. However, if he retains power next May, Macron is expected to institute a series of public sector austerity measures that risk stoking further civil unrest.

As Angela Merkel’s 16-year reign comes to an end in Germany, France is expected to take the initiative in spearheading European politics. Having been appointed to preside over the EU Council from January, Paris will oversee the deployment of the EU’s COVID-19 economic recovery plan. During the pandemic, the EU temporarily suspended tight fiscal regulations so that governments could keep their economies afloat and protect employment. As restrictions ease and the world economy continues to reopen, the EU must remain economically prudent in a sustainable bid to avert an economic disaster reminiscent of the previous Eurozone financial crisis of 2010-12. That said, the potential for future waves of infection holds the capacity to scupper economic progress altogether.

Under the aegis of the French, the EU must look to manage problematic relations with both its members and neighbours. In 2021, increasingly autocratic governments in Poland and Hungary demonstrated both their willingness and capacity to undermine the EU’s legal authority. Should rogue operators continue to impinge on EU law, the resolution of political disputes risks taking precedence over the more useful functions of the European parliament. Much will depend on how the EU responds to rule-breaking; imposing internal sanctions shows resolve, but risks the escalation of diplomatic disputes. Finally, Europe’s political security is equally susceptible to external threat. Just beyond the horizon, Russia continues to wield economic leverage over Europe. The construction of Nord Stream 2, which will channel Russian gas through mainland Europe to Germany, is still scheduled to go ahead, despite Putin’s growing disregard for human rights and international law. Ukraine has argued that the project threatens its internal security, which remains vulnerable at present to the 100,000 Russian troops deployed near its border. Russia’s threat to Europe extends to the cyberspace, and in 2022, Moscow is likely to advance its cyberwarfare campaign into European territory. This year, Russian hackers were accused of leaking sensitive information belonging to the Polish government and interfering in the German election.

Asia and the Pacific

Key Event: 20th Chinese Party Congress

Key Risks: International Conflict, Economic Instability, Cyberwarfare, Civil Unrest

The coming year is likely to mark a continuation in hostilities between China and the U.S, one that threatens commercial operations in the Asia-Pacific region and reinforces the risk of international conflict. Diplomatic contention is expected to manifest itself in the form of a prolonged trade war, military antagonism in the South China Sea, and the intensification of Chinese cyberwarfare operations in the West. In the Philippines, the upcoming presidential election, set for May 2022, risks rekindling civil unrest.

Domestically, the autumn of 2022 will coincide with the 20th Chinese Party Congress, where President Xi is expected to declare whether he intends to stay in power beyond the next five years. On the international stage, China and the U.S. will continue to grapple for influence in the Asia-Pacific region where Taiwan will remain the focal point of contention. In 2021, China’s provocation of the island has grown more audacious as the year has worn on. In October, to herald China’s national day, the military flew Chinese fighter jets and bombers into Taiwanese airspace, fuelling fear of an impending invasion. Military action has been matched by belligerent rhetoric; in July President Xi promised to “smash” any Taiwanese attempts at formal independence. Mr Xi may consider the national congress, penned to begin in the autumn of 2022, to be the perfect time to once again signal his intentions regarding Taiwan. However, although diplomatic and military contention are likely to escalate, the ongoing dispute is not expected to culminate in all-out war.

Beyond the South China Sea, hostility between China and the U.S. is likely to spill over into ulterior domains. The U.S has already announced a diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Winter Olympic Games in February, with Australia quick to follow. Biden’s political allies may feel compelled to follow suit in a clear gesture that signifies the growing disjunction between China and the West. If fraught diplomatic ties continue to deteriorate, the existing trade war may become exacerbated, endangering the business operations of companies not only in the Asia-Pacific region, but all over the world.

Moreover, the magnitude of China’s global cyberwarfare campaign is expected to amplify. There will be a considerable risk of Chinese interference in the Philippine presidential election, on 09 May, which should signal the end of Rodrigo Duterte’s tumultuous six-year rule, a period stained by a brutal war on drugs and the subversion of democratic institutions. The front-runner for the presidency is Ferdinand Marcos Jr., son of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos. Sara Duterte, daughter of the incumbent president, has thrown in her hat in for the vice-presidency. The resurgence of clan politics in the Philippines signals alarm for the future of national democracy. It also creates a risk of stoking civil unrest; opposition groups are already appealing to the electoral commission to bar Mr Marcos Jr. from running due to outstanding charges for tax evasion.

Middle East

Key Event: Lebanese Parliamentary Election

Key Risks: Internal Conflict, Civil Unrest, Travel Disruption, Economic Instability, Terrorism

As 2021 draws to a close, Lebanon faces an alarming growth in civil unrest and internal conflict, an emerging humanitarian crisis, and the prospect of trying to salvage a collapsed economy. The Lebanese parliamentary elections, expected to take place in March, offer the possibility of salvation, but pose a heightened risk of internal insecurity, especially from Iran-backed Hezbollah who may use their external influence and military potency to subvert the election. During the campaigning period, political brinkmanship from the leadership of Lebanon’s competing political parties will continue to foment civil unrest. In Iran, revived negotiations on the nuclear deal will continue into 2022. If unsuccessful, the country’s economic problems could become further aggravated. Finally, the potential re-emergence of terrorist activity in Afghanistan is a cause for concern both domestically and abroad.

In Lebanon, civil unrest has been on the rise since widespread protests first erupted in October 2019 when aggrieved citizens took to the streets to express their outrage against rising taxes and public sector corruption. Demonstrations spiked again after the blast at the port of Beirut in August 2020 led to 218 deaths and unprecedented infrastructural damage, and clashes between rival political factions have elicited firearms violence and subsequent police brutality. The electoral period is likely to be marred by further protests between supporters of Hezbollah and the Lebanese Forces party (LF), which already risk spiralling out of control.

Political contention has recently ground parliament to a halt. Ongoing disputes surrounding the nature of the investigation into the port blast have led Hezbollah representatives to boycott parliament. Najib Mikati, who took over as prime minister in September, presides over a government that has failed to convene since early October. The 2022 election is susceptible to political violence; Tehran-backed Hezbollah is the most powerful military force in the country and could opt to either postpone the election, or vote with its feet if it feels that its parliamentary majority is imperilled. Current data indicates that this may be the case as Hezbollah’s main ally, the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), faces plummeting support. In such an eventuality Iran may interfere in a bid to shape the electoral results. Irrespective of the outcome, the incoming government will face the enormous task of placating civil dissent and overhauling the country’s finances. GDP sunk by 25% in 2020 and the Lebanese Pound recently depreciated to record levels. In order to avert an oncoming humanitarian disaster and stabilise the economy the government will need to negotiate access to IMF loans. If not, food insecurity and medical shortages risk plunging millions into acute poverty.

Elsewhere in the Middle East, Iran faces its own risks heading into 2022. Talks with the West to revive the nuclear deal resumed at the end of November. The previous deal (JCPOA) was abandoned by Trump in May 2018, leading to a revival of harsh U.S. economic sanctions against the Iranian regime. Washington is keen to rekindle the deal, as is Ebrahim Raisi, Iran’s new president, who seeks respite from growing civil pressure. However, unless Iran is able to compromise on its demands, a new deal is improbable. A consequent exacerbation of Iran’s economic woes is likely, as is an internal upsurge in anti-Western sentiment. Finally, concerns remain over whether Afghanistan is to become, once again, a haven for terrorism in 2022. International observers are particularly worried about the potential resurgence of al-Qaeda and ISKP, whose activity imperils both those on the ground, and global targets.

Africa

Key Event: COVID-19 Vaccination Programme

Key Risks: Travel Disruption, Medical, Economic Instability, Civil Unrest, Crime, Internal Conflict, Terrorism

The greatest collective threat facing Africa in 2022 will be that of COVID-19. Due to a dearth in medical supplies and low vaccination rates, Africa will remain inordinately vulnerable to dangerous coronavirus mutations, such as the recent Omicron variant, which could invoke harmful travel restrictions as well as a delay in the continent’s economic recovery. In Nigeria, rampant violence, disorder and terrorist activity threaten to push the country into a state of ungovernability, and in Ethiopia, as the civil war refuses to abate, political fragmentation will become increasingly likely. Finally, security in the Sahel region will continue to be compromised by terrorist-related activity.

Inequitable vaccine distribution means that just 277 million Africans have been vaccinated, approximately 6% of the population. The African Union has been a vocal critic of vaccine nationalism, which not only leaves African countries vulnerable to future waves of infection, but is also likely to hamper economic recovery in 2022 and beyond. The multinational vaccine equity programme, COVAX, hopes to make 1.2bn doses available to lower-income countries in the first quarter of 2022. In addition, China has pledged Africa a donation of some 600m vaccines, as well as opening up another 400m for purchase. However, African countries will still face a significant deficit of both vaccines and medical equipment, leaving them disproportionately susceptible to medical, economic and travel shocks for the year to come. Inconsistent international travel policies will impact business operations, deter investors, and encumber the recovery of the tourism industries. Economic pressures are vulnerable to sliding into civil unrest, and low rates of vaccination provide a breeding ground for viral mutations.

On opposing shores of the continent, two of sub-Saharan Africa’s largest powerhouses Nigeria and Ethiopia face an uncertain year ahead. In Nigeria, the internal security environment has become untenable. The government faces an unremitting threat of terrorist insurgency in the north-east from Boko Haram, and, increasingly, Islamic State of West Africa Province (ISWAP), as well as a secessionist movement in the south, and pervasive civil disorder within both urban centres and rural areas. As the security situation continues to degenerate, Nigeria must contend with an escalation in crime and violence, as well the disintegration of state authority in vast swathes of the country. Meanwhile, Ethiopia may well spend 2022 embroiled in civil war as international peace-brokers repeatedly fail in their attempts to facilitate dialogue. Political fragmentation along ethnic lines will become an increasingly likely possibility.

In the Sahel, Jihadist operations have fanned out relentlessly across Mali, and deep into neighbouring Niger and Burkina Faso. Military rulers in Mali have promised to hold an election in 2022; however, the election has already been delayed once, stoking fears that it may never transpire. In the meantime, such political instability in the region is only likely to add fuel to the fire of insurgency.

The Americas

Key Event: Brazilian General Election

Key Risks: Civil Unrest, Internal Conflict, Travel Disruption, Crime

The Brazilian general election, to be held in October 2022, will mark the centrepiece of next year in South America. The election, which will pit the incumbent president, Jair Bolsonaro, against former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, will create multifarious implications for Brazil’s risk environment. During the campaigning period, the country is likely to experience a wave of civil unrest; demonstrations pose a high risk of degenerating into violence, causing sporadic disruption to travel and an escalation in crime. The election itself constitutes a pivotal moment in the history of Brazilian democracy; although unlikely, the vote may be subject to either fraud or subversion. In the United States, the legislative midterms, to be held at the end of the year, are likely to coincide with a spate of civil unrest.

As the Brazilian election in October closes in, public protests, which have been widespread in 2021, are likely to persist. Civilian grievances against Bolsonaro are manifold; he is accused of undermining environmental sustainability, engaging in corruption, and mismanaging the COVID-19 pandemic, causing hundreds of thousands of needless deaths. Numerous petitions have been filed for his impeachment, and in October, an investigation by the Senate into his handling of the pandemic deduced that he is responsible for “crimes against public health”. The election period risks becoming fraught with political violence.

During the 2018 election, Bolsonaro’s Social Liberal Party engaged in the harassment of opposition political candidates, as well as journalists and activists. He may wish to deploy similar tactics this time around. If he loses the election, Bolsonaro may refuse to stand down from power altogether. Recent months have seen the promotion of military personnel to important ministerial positions, as well as threats from Bolsonaro to use military force to shut down the supreme court that recently authorised an investigation into his presidential conduct. In September, Bolsonaro declared that “only God will remove” him from power; if he keeps his promise the 2022 elections will be a test of Brazil’s democratic resolve. Finally, October’s vote holds serious consequences for the future of the Amazon, which has experienced unparalleled levels of destruction during Bolsonaro’s tenancy.

Elsewhere in South America, social discontent, which sparked mass protests this year, is expected to run on into 2022. In Chile, the resumption of civil unrest will be determined by the outcome of the ongoing Chilean general election, in which polls currently indicate an advantage for the left. Elections are also poised to take place in Colombia and Costa Rica.

In North American politics, next year’s calendar will be dominated by the U.S. mid-terms in November. If the Democrats lose their super majority in the Senate, as is expected, it will effectively impose a block on their jurisdiction to pass legislation. They are also forecast to cede seats in the House of Representatives. The ensuing political stalemate is likely to increase public animosity over contentious issues such as immigration and reforms to the criminal justice system. At a time when former president, Trump, is expected to begin reviving his profile in advance of the next presidential election in 2024, the U.S. will face an escalation in civil discord and corresponding unrest.

Author: Ed Soane, Risk Analyst, NORTHCOTT GLOBAL SOLUTIONS

Contact: risk@northcottglobalsolutions.com

Northcott Global Solutions provides risk assessments, tracking, security escorts, personal protective equipment, remote medical assistance and emergency evacuation.

DISCLAIMER:

Material supplied by NGS is provided without guarantees, conditions or warranties regarding its accuracy, and may be out of date at any time. Whilst the content NGS produces is published in good faith, it is under no obligation to update information relating to security reports or advice, and there is no representation as to the accuracy, currency, reliability or completeness. NGS cannot make any accurate warnings or guarantees regarding any likely future conditions or incidents. NGS disclaim, to the fullest extent permitted by law, all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on content and services by any user with respect to acts or omissions made by clients on the basis of information contained within. NGS take no responsibility for any loss or damage incurred by users in connection with our material, including loss of income, revenue, business, profits, contracts, savings, data, goodwill, time, or any other loss or damage of any kind.